THREE YEARS IN THE PACIFIC; INCLUDING NOTICES OF BRAZIL, CHILE, BOLIVIA, AND PERU.

BY AN OFFICER OF THE UNITED STATES NAVY.

PHILADELPHIA

CAREY, LEA & BLANCHARD

1834

|

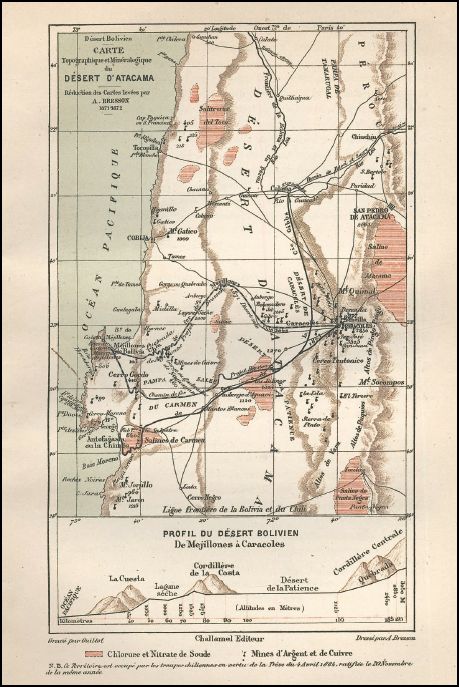

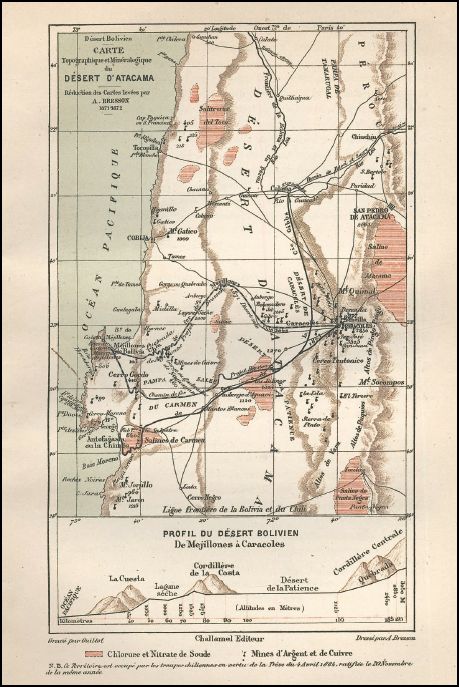

Carta topográfica y mineralógica del Desierto de Atacama confeccionada por Andrée Bresson en los años 1871-1872,donde se destacan los yacimientos de salitre, plata y cobre conocidos. Publicado en “Bolivia Sept annéesd’explorations, devoyages et de sejeursdans L’AmeriqueAustrale en París, 1886”.

Crédito: Cobija, nacimiento y desarrollo... |

ADVERTISEMENT. The following pages are the result of observations made during two cruises in the Pacific Ocean, one of more than three years, on board of the U. S. S. Brandywine, from August 1S26, to October 1829, and the last on board of the U. S. S. Falmouth, from June 1831, to February 1S34, and recorded with a hope of making my countrymen better acquainted with some of the peculiarities of their southern neighbors. As far as the nature of the work would permit, the author has avoided obtruding himself upon the attention of the reader, and has indulged in but few reflections ; being content to pre- sent naked facts, and allow each one to dress them for himself, and draw his own conclusions. The merits of the perform- ance, with its many imperfections, remain to be decided by the public, from whom is claimed all the indulgence usually accorded to novices in undertakings of the kind.

[...]

CHAPTER I.

Bay of Mexillones -- Cobija -- Soil -- Landing -- Balsa -- Town -- Old trees -- Scarcity of water -- Commerce -- Visit to the copper mines -- Catíca.

We sailed on the 5th of September from Coquimbo, with a northerly breeze, which lasted about twenty-four hours, when the usual trade commenced, but it was so light that we did not reach the bay of Mexillones till late in the evening of the ninth. This is a beautiful, extensive, and deep bay ; the anchorage is close in to the shore, and so smooth that it offers some advantages to ships of war to careen and paint, as their crews may be put on shore without any danger from desertion. The nearest town or habitation is the port of Cobija, more than half a degree to the north. The bay opens to the northward, and is surrounded by high land, as barren as can well be ima- gined. There is not a blade of grass, nor even a cactus to be seen on it. Nor is there a drop of fresh water to be found within many leagues. The bay has been frequently examined, with a view of making it the port of Bolivia, but the idea has been as frequently abandoned, from the want of water. There is a small stream about twenty leagues from it, which, it is said, might be brought here. At present, the only inhabitants are the varieties of sea birds, pelicans, gulls, cormorants, and condors, and the only regular visiters are whales. Occasionally a vessel anchors here, in order to avoid running past Cobija in the night, when they gain this latitude (23° S. ) too late to reach the port on the same day. This was our own case.

On the morning of the tenth it was calm, and though we fanned out of Mexillones, we lay off Cobija all night, and did not anchor till near three o'clock on the afternoon of the eleventh. The Port of Cobija is difficult to be found by strangers. About five miles to the southward, are two low white rocks, which are the only land marks at this season of the year, when the profile of the mountains of the coast is almost constantly shrouded in fogs or clouds. So soon as a vessel is descried from the fort, a white flag is hoisted on the point as a mark, which may be seen ten or twelve miles at sea.

The roadstead of Cobija is formed by a short low point of rough jagged rocks, on which stand the flag-staff, and a fortress mounting six long guns. The anchorage, though secure, and at a short distance from the shore, is not good. Vessels, in " heaving up," frequently part their cables, or break their anchors. About six miles to the northward is another rocky point, behind which, vessels that load with copper ore from the neighboring mine, lie, though not very comfortably. This spot is called Catíca.

Near the first point is the town, built upon the falda or lap of the hills, or, we would say, mountains, which rise abruptly to a height of between three and four thousand feet, barren, cheerless, and naked, except in the region of the clouds, where a few blades of grass have struggled through the soil, nourished by the dews of winter. The trees of cactus grow larger than any I have before seen. Even these patches of green fade and are burnt up in the summer under a tropical sun. The color of the mountains is variegated in spots of reddish, greenish, and whitish earth, with stria? running down the sides, looking like the beds of little cascades, or streams formed by heavy rains : the captain of the port informs me, however, that showers are unknown, and the only rain is a heavy mist like the "llovisna," or drizzle of Lima --and even this is absent during the greater part of the year. The lap of the hills, which extends from their base to the sea, not exceeding half a mile in breadth, appears to be formed by the accumulation of earth and stones, washed and rolled down in the course of time ; and a walk on shore corroborated this opinion. Along the street we saw several shelving strata, formed of large pebbles of a greenish color, bedded in a cement of dry earth, resem- bling a mammoth puddingstone formation. The rocks about the place are hard, dark, green-stone, and every where bear marks of having been worn smooth on their angles by the sea. In fact, towards Catíca, there is a kind of natural wall, some two hundred feet high, that has evidently been under water at some remote period. Fancy a stiff mud or ooze, worked up with shells and pebbles of every size, and then left to dry, and you will get an idea of this bank or wall. Another curious formation in the neighborhood, is of very small shells, which when carelessly examined presents a texture similar to a coarse flag stone, but a nearer inspection shows you the minute shells, some of which are sufficiently perfect to be very readily classed. The metallurgist at Catíca stated that this formation was a phosphate of lime, and that square slabs of it were used for the flooring of their furnaces, and also ground fine, and mixed with mud or clay, to form fire bricks.

The landing is effected by pulling through a belt of kelp, which lines the shore of the bay, and through a narrow channel, between some low black rocks, into a smooth little basin, where the boat is drawn up on the sand beach. So soon as we stepped ashore, our attention was drawn to a fisherman, who was filling his balsa with air. He was a short, square built Indian, pretty well advanced in life, with long locks of black and gray hair hanging straight from under a low-crown-ed narrow-rimmed straw hat, rather worse for wear. He wore a short jacket and still shorter trovvsers of old blue cloth, and the particolored remains of a poncho girded his loins. A dark copper colored skin covered his face and neck, and though far from being

embonpoint, as Bolivians generally are, he might be called muscular. His nose was flattened and pinched in, just as it joined the os frontis, but it did not present the African flatness ; and the angle of his face was that common to the Caucasian or European race. His eyes were small, black, and widely separated from each other, and though he did not squint, their axes seemed to incline very much towards each other. Add high cheek bones and a regular turn to the figure, and you may form some idea of a Bolivian--at least such is the general appearance of those I have met. There is, however, nothing fierce about them ; but on the contrary, there is a pleasant, good humored convivial expression which speaks in their favor. This worthy fisherman was resting on one knee beside his half flaccid balsa, with a small tube of intestine, which is attached to its end, in his mouth, blowing and puffing, and occasionally tapping the vessel to ascertain how the inflation proceeded. At length he finished, and twisted the tube round the nozzle which attached it to the balsa.

The balsa used here is similar to that of Coquimbo, but larger, and decked over between the two bags of wind by a dry ox hide or seal skin. On this they carry freight or passengers perfectly dry. To prevent the water from penetrating, the balsa is coated over with a pigment resembling new tanned leather in color. Another fisherman drew his balsa ashore, and threw three fine large fish upon the sand, which he had caught amongst the rocks off the point, with a harpoon. He told us that was the only way of taking them.

The bay affords a variety of excellent fish, and the rocks are full of shell fish, much esteemed by the natives, but not eaten by foreigners. Amongst them are a variety of limpets of a large size, as well as many smaller shells. Our stay here, however, did not afford us time to collect any except a few dead ones; --but I am inclined to think, that an amateur would be rewarded by a few days' labor at this place.

We walked towards the governor's house, which fronts the landing, and turning to the left, found ourselves in the main and only street of Cobija. It is perhaps a quarter of a mile long, but not closely built. The houses are all one story higb, and constructed of wood and of adobes in the simplest style, and very few of them have patios. The plastering is mixed with salt water, and very soon blisters and peels off, from the effects of the sun, and therefore a constant repair is necessary. Wood, all of which is brought from Chiloe and Concepcion, is a cheaper material for building than adobes, both on account of repairs and the original cost. A great proportion of the houses are occupied as stores, where a great variety of foreign goods, both European and American, are exposed for sale. About the middle of the street, there are two ancient palms, and an old dried up fig tree, (described by Frezier, in 1713,) on the bark of which foreigners have been in the habit of cut- ting their names. Some of these bear date as early as 1809. Amongst other names is that of the U. S. S. Vincennes, 1828, and P. White, N. Carolina, 1832.

The oldest building here is a church, said to have been erected a hundred and fifty years ago. It is built of adobes of a small size, and the cement is said to have been made of the shell formation mentioned above, and is now harder than stone. This temple is very small and mean in appearance ; and opens to the sea by the only door in the building, which is double, and secured by a common padlock ; in fact, unless attention were called to it, it would be overlooked as some stable.

Amongst the inconveniences of this port, perhaps the greatest is the scarcity of water, which is barely sufficient for the daily consumption of the present small population, and even this is so brackish, that strangers are unable to drink it without a pretty free admixture of wine or spirits. Coffee and tea made from it are far from being very palatable. In former years, however, it was not so scarce. The springs from which it is obtained are in front of the trees in the side of the hill, and secured by lock and key, except a small tube of the size of a gun barrel, from which a stream as large as a swan quill issues; and this is carefully stopped when not running into the bottles or other vessels of those who come for water. At the end of the street, and within ten yards of the surf, is a well, said to contain the best water in the place: this the governor has appropriated to his own use, and that of the garrison, not exceeding, in all, servants included, fifty persons. About a half a mile from the town is a spring, which is used for washing and watering the cattle. A barrel of sweet water from Valparaiso or Peru is esteemed no small present, and the favor is frequently asked of vessels arriving in the port. There is now an American ship at Catíca, loading with copper ore ; the captain fearing that he should be short of water for his voyage, went in his boat twelve miles to leeward, and was absent two days, and obtained only two barrels of water, which he declares "is so salt and hard, that it will not even boil beans!" The saltness of the springs is owing to the beds of nitre and salt in the neighborhood, through which the water percolates to the place of its exit. Although there is a very complete apparatus here for boring, and with a reasonable prospect of success, it has never been tried.

In the United States, a tavern and a blacksmith's shop will always form the nucleus for a village. In South America, a church and a billiard table answer the same purpose, and poor is that place indeed, where, during some part of the day, the balls are not heard rolling about. Here there is a tolerable table, but very illy supplied with cues ; and as in all Spanish towns, the pin-game is the only one played by the natives. This game is played with three balls. Five pins of hard wood, called "palillos," each five inches long, and a half inch in diameter, are set up in the centre of the table, with sufficient space between them to allow a ball to pass easily through. If the centre pin be knocked down without disturbing either of the others, placed on the corners of a square, it counts five, provided the player's ball first strike the spot ball or that of his antagonist ; if not, he loses as much. The fall of either of the other pins, or all of them together, counts two each.

There is a tavern here, where all the foreign residents eat, finding it much less trouble, and more economical, than maintaining a private table. Though rather scanty in furniture even for the table, a very good fare is served up in the Spanish style. Some idea of the trouble of house keeping, may be had from a knowledge of the fact, that every thing, except butcher's meat, is brought from Chile and Peru. Every vessel, particularly the coasters, from both those countries, brings large quantities of vegetables and live stock for this market, and a part of that is sent off to the interior! Meat and fodder for the cattle, used in the mining and commercial operations, are brought from Calama, a town forty leagues to the eastward of the coast ; and between it and the coast, I am told, there is not a habitation, a tree, nor a blade of grass, nor a spring of wholesome water!

The latitude of Cobija is 22° 30' south. It is the only port of the Republic of Bolivia ; whose limited coast, extending from 21° 30' S. to 25° south, does not afford any site so convenient as this. It is placed in the desert of Atacama, one hundred and fifty leagues from Chuquisaca, the present capital; three hundred from La Paz, the former capital, and a hundred and fifty from the far famed Potosi, and not less than seventy leagues from any well cultivated lands. It was declared to be the Port of Bolivia in 1827, but from the scarcity of water and provisions, and from the interruption which the trade received from the war with Peru, very few vessels entered it before 1829, since which time the place has increased to a population of between six and seven hundred persons, including the miners in the immediate vicinity -- and from the number of new buildings going up, we should draw very favorable conclusions relative to its prosperity. Though so recently declared the port of entry for Bolivia, Cobija was resorted to as early as 1700, by French merchant vessels, when a very rich commerce was driven between it and the mining district of Potosi. At that period water was in greater abundance, and of a better quality than at present. Previous to 1827, the Republic received all its supplies of foreign goods through the port of Arica, in Peru, by way of the interior town Tacna.

A half million of dollars, in foreign productions, is estimated to pass through this place annually for the interior. Packages are almost all unpacked, and again put up in smaller parcels, and of a certain weight, to accommodate them to the means of transportation, which is entirely by mules and jackasses. They are generally carried on jackasses as far as Calama, and from thence on mules to the different points of destination.

The imports consist of European dry goods, cottons, silks, quicksilver, tobacco, teas, wines, American domestics, flour, &c. These are frequently purchased on board at Valparaiso, deliverable at this port. The duties are low now on every thing, and the question of making it an entirely free port, is agitated in the present congress. All kinds of provisions, except luxuries, as wine, &c, are admitted free. Manufactured goods, as furniture, and American cottons, pay an

ad valorem duty of ten per cent, which is the highest levied ; silks and similar goods pay five. The exports are confined to coined gold and silver, which pay a duty of two per cent, (in bullion they are prohibited,) and copper and copper ores. The following table, the information for which was obtained from the captain of the port, exhibits a view of the number of vessels which have visited ihis port from the 1st of November 1831, to September 14 1832, being ten and a half months.

Nation. Ships. Brigs. Schooners.

Peru, -- 4 13

United States 7 3 8

Chile -- 2 13

England 3 3 --

France 6 3 --

Holland -- 1 --

Mexico -- -- 1

Colombia -- 1 --

Buenos Ayres -- -- 1

Russia 1 -- --

Sardinia -- 1 --

Hamburg -- 2 2

From the 9th of March 1831, to the 14th September 1832, being seventeen months, ten ships, ten brigs, and three schooners, under American colors, have visited this port, and some of them several times.

|

| Fondeadero de Tocopilla, embarcaciones salitreras. Finales del siglo XIX |

During our stay here, a day was devoted to a visit to the mines. Having prepared a basket with some cold meats, wine, water, &c, we left the ship in the gig, and pulled to Catíca, which is about two leagues from the anchorage. At this place the landing is bad, and generally effected through the surf on balsas. The captain of the American ship before mentioned, loading copper ore for Swansey, Wales, joined our party. We examined the bellows furnace here, and a heap of ore, which they were weighing and embarking. It consisted of a brown oxide, with a hard clear fracture, and a red oxide, a sulphuret, and some green carbonate.* Smelting is not carried on to any great extent, from the scarcity of fuel. There is no mineral coal in the country, and the charcoal is brought from Chile and Peru. For the purposes of cooking, the wood of the cac- tus is used. It is very light, and affords but little heat.

We proceeded to the foot of the hill, upon which the mines are situated, distant a mile and a half from Catíca. The road is quite rough, and crosses a gap or mouth of a valley, through which passes the road to Calama and Potosi. When arrived at a shed, which is built at the foot of the hill, we found we had ascended perhaps three hundred feet above the level of the sea, and had a view of the highway till it winds out of sight amongst the hills. From the nature of the soil, from the great quantity of pebbles strewed over it, and other features of this road, we came generally to the conclusion that it had once been the bed of a river, or a mighty mountain torrent. After a short rest, we began to mount the side of the hill by a zigzag pathway, which ascends at an angle, from the base, of at least thirty-six degrees. From the starting place, we could just perceive, a thousand feet above us, and not half way to the top of the hill, a small white tent, amidst some large trees of cactus, which was the goal of our labors. Many paths are formed by the miners and mules on every part of the hill, and some of them are much more steep than others ; that which we followed, is perhaps the least difficult of ascent. We were forced to stop for breath very frequently on our way up, and at such times we observed the mouths or entrances of several mines, which had been opened, but not now worked. Some of them are not more than fifteen or twenty feet deep. After considerable toil we reached the tent. A half dozen little hovels, just large enough for two or three persons to crawl into,

* The gentlemen engaged in the business permitted us to select some speci- mens, and presented us with others which had been laid aside. We obtained some fine crystals of the oxides, and a half dozen pieces containing very mi- nute portions of native gold. These ores are supposed to yield about 25 per cent, of copper, and to contain gold enough to pay the expense of reducing it.

were built about it, with loose stones and branches of the cactus. Amongst these were perhaps twenty women and children, seated upon stones, surrounded with small heaps of ore, which they were breaking up, and sorting and throwing away the stone which adhered to it. They used double flat faced hammers, of about three pounds weight. Three or four " boca minas," or entrances to mines, opened near each other, and before them were piles of ore, thrown by those employed in bringing it up. The whole scene was one of wretchedness. The women and children were coarsely dressed in woollen, and without the slightest shelter from the hot sun.

We descended to the bottom of one of the mines. A miner carried a small, dirty, smoking lamp, and led the way. About forty feet from the entrance, it turned to the left, and we found ourselves in a spot where the sides of the mine were lined with thin plates of quartz crystal, which dip into the joints or cracks between the pieces of ore, and our lamp seemed sudden- ly to multiply its light a hundred fold. If the walls had been hung with cut glass drops, it could not have been more beautifully irridescent. When I arrived near the bottom, the guide suddenly left me to return for some one of the party, who had not progressed so fast. He was absent a half minute, and I was in total darkness. Close to me I heard a man snoring, and almost under my feet, the blows of a hammer, accompanied by that subdued short breathed sound of " ha!" at every blow. To one unused to such circumstances, there was something appalling and unpleasant to the feelings. The light soon returned, and another turn through a hoie just large enough to pass, brought us to a miner lying with his side against the earth, in a bent position, breaking out large pieces of ore from above his head, with an iron chisel, and heavy hammer. It was he whom I heard when alone in the dark. He handed us a piece of the ore, which he had just broken out, for examination, and broke us a neat specimen of what he termed the best. This was the dark heavy oxide, with a thin laminum of quartz spread over one side.

The course of this mine falls very little below a horizontal line, and is about ten feet in diameter in some places, and in others much narrower. From the surface to the bottom, does not exceed a hundred and fifty feet. The gangue of these mines is either granite or carburet of iron.

After indulging our curiosity, and selecting some pieces of ore to carry with us, we entered one of the little huts where the servant had deposited the basket of provisions. Five in all got inside, including our host, who was polite, and answered readily the questions proposed to him. Exercise had given us an appetite, and it was not long before the contents of our basket (of which also the host partook) disappeared. The hovel contained a small chest, a dirty bed, and a small barrel, and this was all the furniture. The ore is brought from the bottom of the mines upon men's backs, in small sacks of hide, and the weight they thus carry up rough ascents, difficult for us to climb unladen, is really surprising. The athletic forms of these men, and their apparent cheerfulness, caused my admiration as much as the severe nature of their toil. There are forty men at work, who are paid each a dollar a day, and considering the life they lead, and the high price of provisions, it is not much. After being culled, the ore is carried on mules and asses to Catíca, to be smelted or exported. On taking a view of the whole, I would not give a few fertile acres in our happy country, for all the mines of this province.

As we descended the hill, we saw several small yellow birds hopping amongst the stones, and picked up a few land shells. About half past three we got back to Calica, all very tired, and quite ready for a cool glass of wine and water, which was kindly given us at the smelting house. Here one of the party was requested to see a female afflicted with a dropsy, which is the prevalent disease of the place, which is otherwise healthy. As there is no medical man in Cobija, they are glad to avail themselves of advice from any physicians who may chance to visit the port. The only leech is the Sangrador, or bleeder at- tached to the garrison, and possibly the curate may have some smattering of the healing art. After resting an hour, and in vain endeavoring to procure a mule, or horse, or ass, we set forward on foot for the town. The road is rough, up hills and over gullies, without anything to relieve the eye from its barrenness. Scarcely a bird is to be seen ; in fact, since our being here, I have seen only three or four buzzards,* a half dozen gulls, and a lone pelican. Instinct or experience teaches, that there is nothing to invite either man or animal â€" but what will not man undergo for gold !

The two leagues were passed, and, well wearied with our excursion, we returned on board at sunset.

|

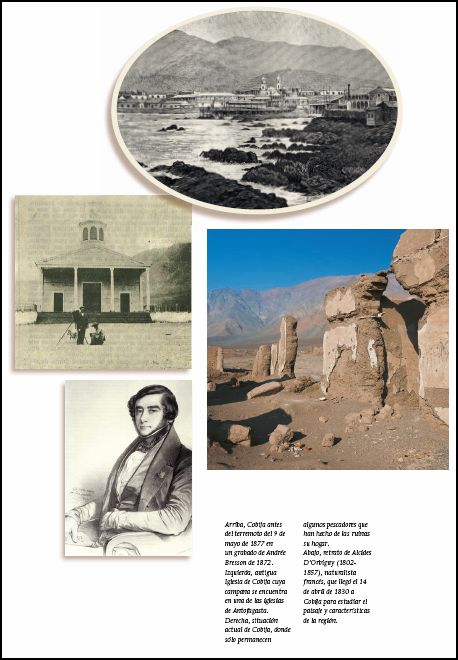

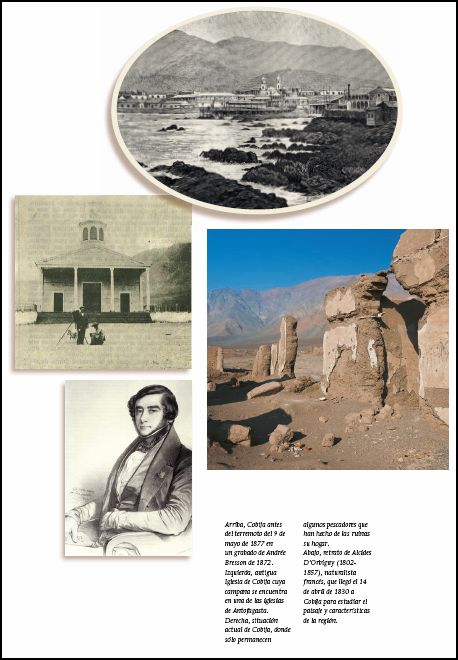

| Arriba, Cobija antes del terremoto del 9 de mayo de 1877 en un grabado de Andrée Bresson de 1872. Izquierda, antigua Iglesia de Cobija cuya campana se encuentra en una de las iglesias de Antofagasta. Derecha, situación actual de Cobija, donde sólo permanecen algunos pescadores que han hecho de las ruinas su hogar. Abajo, retrato de Alcides D’Orbigny (1802-1857), naturalista francés, que llegó el 14de abril de 1830 a Cobija para estudiar el paisaje y características de la región. Crédito: Cobija, nacimiento y desarrollo... |

CHAPTER II.

Historical sketch of Bolivia -- Its productions -- Coca.

On the 5th of August 1825, Potosi, Charcas, Cochabamba, and Santa Cruz, formerly constituting Upper Peru, declared themselves independent of Ferdinand VII., and on the 11th of August, the Assembly decreed that the Republic should bear the title of Bolivia. They date the birth day of the nation from the 6th of August 1825, the day on which was gained the victory of Junin. On the 25th of May, 1826, a Congress was installed at Chu- quisaca, and a committee appointed to examine the Constitution proposed by Bolivar. They reported favorably, and in conformity to its principles, a President was chosen for life. The choice fell on General Sucre, who accepted the office for only two years, on the condition that two thousand Colombian troops should be permitted to remain with him. Sucre declin- ed holding the presidency for a longer period than two years, on the grounds of having been educated a soldier ; and having spent the greater part of his life in the field, he was unfit to be the civic chief of their government.*

*

Memoirs of General Miller.

During his administration, schools were established, and plenipotentiaries were sent to Buenos Ayres, to obtain the acknowledgment of the independence of the Republic, which was withheld by that government, alleging that Bolivia could not be free while General Sucre and two thousand Colombians were permitted to remain within her territories. This act gave umbrage to the Bolivians, and evoked some spirited articles on the subject from them, which appeared in "El Peruano."

On the 15th of October 1826, Peru acknowledged Bolivia to be an independent state. At present, an agent from Brazil, and a Charge d'Affaires and Consul General from France, are residing at Chuquisaca. The government of the United States has not yet sent a diplomatic agent of any class to that country.

Notwithstanding that Peru acknowledged the independence of Bolivia, she was anxious to obtain the cession of certain territories, adjoining to her southern boundary. On the 9th of April 1827, the Peruvian plenipotentiary left La Paz, and soon after, a Peruvian army, under the command of General Gamarra, appeared on the Bolivian frontier. On the 18th of April 1828, the garrison at Chuquisaca, the capital of Bolivia, revolted, through the intrigue and machinations of the Peruvian general. This garrison consisted only of fifty men, yet it was sufficient to overthrow the then existing government. General Sucre, in attempting to quell the disturbance, was severely wounded in the arm. Gamarra, under pretence of fear for the personal safety of the President, and anxiety to restore tranquillity to the state, marched from the Desaguadero, where he was encamped, and took possession of La Paz, and of the Capital. Sucre at once resigned, and sailing from Cobija, arrived at Callao on the 13th of December, where he remained twenty-four hours, but was not permitted to land. While there his wounds were dressed by one of the medical officers of the United States Frigate Brandywine ; and he offered his services to intercede between the governments of Peru and Colombia, then at war, with the hope of restoring peace without having recourse to arms. On the fourteenth he sailed in the Porcia (an American ship) for Guayaquil.

Bolivia was soon plunged in a most dreadful state of anarchy. General Santa Cruz was called by the constituent Congress to be President, but a party, or rather a faction, forcibly elevated General Don Pedro Blanco to the chief magistracy. On the 25th of December he made his public entry into Chuquisaca, and the next day took the oath of office. On the thirty-first a revolution took place, he was made prisoner, and on the morning of the 1st of January 1829, he was shot, after having been President four days!

On the 14th of December 1828, Gamarra was received at Lima, amidst the rejoicings of the people, who styled him the Liberator of La Paz, and entertained him at the theatre, and at the Plaza del Acho with a bull-bait.

On the 15th of February 1829, (six weeks after the death of General Blanco,) the Vice President dissolved the Conventional Assembly, and declared all their acts to be void, leaving the laws the same as at the adjournment of the constituent Congress, and named again General Santa Cruz as the provisional President.

Since that period, Santa Cruz has been at the head of the government, which for prosperity ranks amongst the foremost of the South American republics. He has established schools, increased commerce by relieving it of many heavy taxes, and he has concluded a treaty of peace and commerce with Peru.

The extensive territory of Bolivia is rich in mines of copper and the precious metals; the vine and olive nourish; in many places sugar cane grows wild, and rice and flax are produced in abundance. Peruvian bark and indigo are successfully cultivated ; and the coca, which is sc essential to the Indian's comfortable existence, is a staple of this climate. The

erithroxylon peruvianas or coca, at the time of the conquest, was only used by the Incas and those of the royal or rather solar blood. The plant was looked upon as an image of di- vinity, and no one entered the enclosures where it was cultivated without bending the knee in adoration. The divine sacrifices made at that period were thought not to be acceptable to heaven, unless the victims were crowned with branches of this tree. The oracles made no reply, and auguries were terrible, if the priest did not chew coca at the time of consulting them. It was an unheard of sacrilege to invoke the shades of the departed great, without wearing this plant in token of respect, and the Coyas and Mamas, who were supposed to preside over gold and silver, rendered the mines impenetrable, if the laborers failed to chew the leaves of coca while engaged in the toil. To this plant the Indian recurred for relief in his greatest distress ; no matter whether want or disease oppressed him, or whether he sought the favors of Fortune or Cupid, he found consolation in this divine plant.

In the course of time, its use extended to the whole Indian population, and its cultivation became an important branch of trade. It produced at one period no less than $2,641,487 yearly, and we are told that its leaves were once the representative of money, and circulated as coin.

It is sown in the months of December and January, its growth being forwarded by the heavy rains which fall in the mountainous regions from that time till the month of April. It flowers but once a year, but yields four crops of leaves, which are not however equally abundant; the least so is gathered at the time of inflorescence. It requires to be sown once in five years. When the leaves attain an emerald green on one side, and a straw color on the other, they are carefully pulled, one by one, and dried in the sun.

The virtues of the coca are of the most astonishing character. The Indians who are addicted to its use are enabled to withstand the toil of the mines, amidst noxious metallic exhalations, without rest, food, or protection from the climate. They run hundreds of leagues over deserts, arid plains, and craggy mountains, sustained only by the coca and a little parched corn, and often too, acting as mules in bearing loads through passes where animals cannot go. Many have attri- buted this frightful frugality and power of endurance to the effects of habit, and not to the use of the coca, but it must be remembered, that the Indian is naturally voracious, and it is known that many Spaniards were unable to perform the Herculean tasks of the Peruvians, until they habitually used the coca. Moreover, the Indians, without it, lose both their vigor and powers of endurance. It is stated, that during the siege of La Paz, in 1781, when the Spaniards were constantly on the watch, and destitute of provisions in the inclemencies of winter, they were saved from disease and death hy resorting to thus plant.

The coca possesses a slightly aromatic and agreeable odor, and when chewed, dispenses a grateful fragrance; its taste is moderately bitter and astringent, and it tinges the saliva of a greenish hue. Its effects on the system are stomachic and tonic, and beneficial in preventing intermittents, which have always prevailed in the country.*

The mode of employing coca is to mix with it in the mouth a small quantity of lime, prepared from shells, much after the manner that the betel is used in the East. With this, a handful of parched corn, and a ball of arrow root, an Indian will travel on foot a hundred leagues, trotting on ahead of a horse. On the frequented roads, I am informed, that the Indian guides have certain spots where they throw out their quids, which have accumulated into little heaps, that now serve as marks of distance; so that instead of saying one place is so many leagues from another, it is common to call it so many quids!

The Indians sometimes have tertulias for taking the infusion of the leaves, as well as for chewing it. In the former mode, the effects are agreeably exhilarating. It is usual to say, on such occasions, "vamos a coquear y acullicar" --let us indulge in coca.

*

Disertacion sobre el aspecto, cultivo, comercio, y virtudes de la famosa planta del Peru, nombrada Coca. For el Doctor Don Hipólito Unanue. Mercurio Peruano. July, 1794. Lima.

[...]